Angela Yoon Seeks Precision Care for Oral Cancer

Every year, 8,000 Americans die of oral cancer. When diagnosed early—at TNM Stage I or Stage II, the five-year survival rate is 60 percent. The other 40 percent, who have a much more aggressive form of the disease, have a poorer prognosis. At present, doctors have no way of forecasting which category a patient falls into, let alone deciding upon a course of treatment based on such information.

Angela J. Yoon, DDS, MAMSC, MPH is aiming to change that.

Dr. Yoon, who is the Director of the Division of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology and the John W. Richter Associate Professor of Oral Pathology (in Dental Medicine and in Pathology & Cell Biology) is working to develop a test to detect the genetic codes that influence a particular tumor’s development so that doctors can forecast the trajectory of a patient’s oral cancer and provide personalized treatment.

Already, Dr. Yoon has identified specific genes that—combined with such risk factors as tobacco and alcohol use—can increase a person’s susceptibility to aggressive forms of cancer.

With her new project, Dr. Yoon intends to take a step further back in the cancer development timeline to examine the non-coding genetic material known as microRNA that controls protein expression, impacting the clinical course of a tumor. By identifying those snippets of microRNA that give rise to aggressive forms of oral cancer, she will be able to measure them and identify individuals whose cancer is more likely to recur or become fatal.

You are about halfway your study to find a microRNA-based marker for aggressive oral cancer. What outcomes do you hope will come from this and related research projects?

I hope to develop a miRNA-based prognostic model and assess its ability to identify, among early-stage cancer patients (as defined by the TNM system), those whose cancer is most likely to be deadly. Right now, we have strong preliminary data in which we identified and validated two prognostic miRNA signatures.

As a next step, we aim to develop the microRNA-based prognostic model and validate it.

From there, we will construct a formula to calculate mortality risk using microRNA expression levels as well as other variables, such as those related to demographics or lifestyle. This will help clinicians give a more accurate prognosis to each patient.

We will also investigate which treatments have the greatest benefit for patients in different risk groups. This will help lead to more personalized treatments for patients, otherwise known as precision medicine. This aligns with precision medicine initiatives at the university as well as at the national scale through the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

How did you get interested in this area of study?

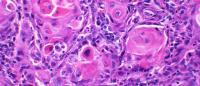

As an Oral & Maxillofacial Pathologist, I examine tissue biopsies under the microscope and diagnose cancer every day. Additional examination and imaging study defines the clinical stage of cancer. But the most common system to define a cancer’s stage—the TNM method, which assesses the size of tumor, presence in the lymph nodes, and metastasis, doesn’t offer an accurate prognosis.

As a diagnostician, I started to wonder if there is any way to tell, by examining tissue biopsies, how likely a patient’s cancer is to be deadly.

I decided to start my own study to answer this important question.

How do you think precision medicine will change the prognosis for cancer patients in the next ten years? The next 20?

Medicine is now coming to understand that you can’t predict outcomes on the basis of a patient’s TNM stage alone.

Instead, it’s the molecular characteristics of the tumor—both genomic and proteomic—that define carcinogenesis, or the progression of cancer.

In recent years we have begun to understand how genetics, the environment, and other factors interact to affect outcomes at the molecular level. My collaborators and I want to diagnose and treat oral cancer patients based on that level of understanding.

By looking at the molecular biomarkers, which correlate with the biology of the disease itself, this could help determine who is high risk and what treatments are best for an individual patient.

Similar work is happening across research arenas. Some people, including Dean Stohler, envision a day when once-deadly cancers can be cured or managed as chronic disease.

What role do you want Columbia to play in that?

Columbia University Irving Medical Center will become one of nation’s leading institutes in personalized diagnosis and precision treatment of oral cancer. Our multidisciplinary team across the fields of dentistry, oncology, pathology, epidemiology, and biostatistics at CUIMC is working hard to make this happen.

You received your DDS at Columbia and were the first student to complete our oral pathology residency program, and have grown in leadership positions since then. What kept you here? And what impact do you want to have on the school?

Amazing mentors and brilliant colleagues, who provided guidance every step of the way, made all the difference. None of these would have been possible if it wasn’t for their support. Soon, it will be my turn to mentor junior faculties and students. I just hope I will be as good as my mentors in providing guidance.

How do you spend your free time? Do you have any hobbies?

I think I used to have hobbies before my two children. Now all my free time is about them.

References

6 in 10 early stage oral cancer patients survive 5 years. The other 4 have a much more aggressive disease, but there is no way to distinguish one from the other. Angela Yoon, DDS, seeks a genetic marker to tell how aggressive the cancer is as a first step toward precision medicine treatment. She answers questions about her work and the future of the field.